Unveiling The Mesopotamia Social Pyramid: Life In Ancient Classes

Ancient Mesopotamia, often referred to as the cradle of civilization, was home to one of the earliest complex societies in human history. This remarkable land, nestled between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, gave rise to groundbreaking innovations in writing, law, and governance. Central to its enduring stability and functionality was a highly stratified social structure, a fascinating system known as the Mesopotamia social pyramid. This intricate hierarchy determined one’s lot, reflecting the daily life, habits, and even the appearance of an individual within this foundational civilization.

Understanding the social structure of ancient Mesopotamia is crucial to grasping how this society thrived for millennia. Unlike modern societies that often champion social mobility, ancient Mesopotamia's social classes were largely rigid, with distinct roles that contributed to the functioning of society as a whole. From the divine kings at the apex to the enslaved people at the very bottom, each layer played a specific part in the grand tapestry of Mesopotamian life. This article will delve deep into the various tiers of this ancient hierarchy, exploring the lives, responsibilities, and significance of each group within the Mesopotamia social pyramid.

Table of Contents

- Understanding Mesopotamia's Stratified Society

- At the Apex: The Ruling Class and Priests

- The Backbone: Free Citizens and the Middle Class

- The Base: Enslaved People and Their Plight

- Daily Life Reflected in Social Standing

- The Dynamics of Stability and Change

- Legacy of the Mesopotamia Social Pyramid

- How Social Class Shaped Identity

- Conclusion: The Enduring Structure of Ancient Mesopotamia

Understanding Mesopotamia's Stratified Society

The social structure in ancient Mesopotamia was highly stratified, meaning it was organized into distinct layers or classes, much like a pyramid. This hierarchical arrangement was not merely a theoretical concept but a tangible reality that shaped every aspect of an individual's existence. From the moment of birth, one's place within this pyramid was largely predetermined, influencing their opportunities, responsibilities, and even their legal rights. The stability of this social hierarchy began to establish itself at a very early period, preserved for millennia by a combination of religious beliefs, economic systems, and political power.

Mesopotamia's social pyramid was not unlike many later civilizations, yet it possessed unique characteristics born from its specific historical and geographical context. The fertile crescent's reliance on irrigation agriculture fostered large, settled communities that required sophisticated organization. This necessity for collective effort and centralized control naturally led to the development of a complex social order. The system was designed to ensure efficiency, order, and the successful functioning of a society that was constantly battling the unpredictable forces of nature and external threats.

The Foundation of Hierarchy

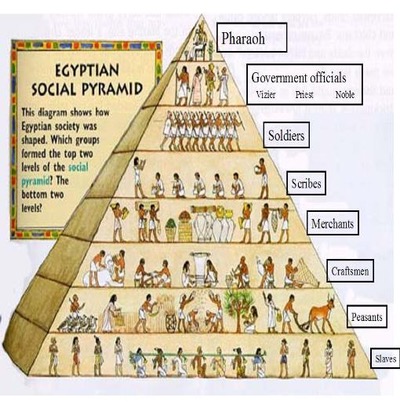

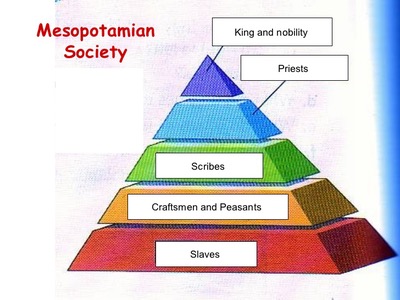

The Mesopotamia social hierarchy basically consisted of three broad classes: nobility, free citizens, and slaves. However, a more detailed examination reveals a finer stratification within these categories, particularly when considering the specific roles and privileges. The social pyramid of ancient Mesopotamia consisted of several distinct layers, each representing different social classes and their corresponding roles. At the top were the ruling class, including kings and high-ranking priests, followed by a middle class of officials, landowners, and merchants, and finally, the vast lower class which included commoners and enslaved people. This structure played a crucial role in the daily life and overall stability of the civilization.

At the Apex: The Ruling Class and Priests

At the very pinnacle of the Mesopotamia social pyramid stood the most powerful and influential individuals. This elite group commanded immense respect, wealth, and authority, holding the reins of both temporal and spiritual power. Their positions were often seen as divinely ordained, reinforcing their legitimacy and ensuring the populace's compliance.

The King: Divine Authority and Earthly Power

The king was the top rank holder, the undisputed head of the Mesopotamia social structure. His role transcended mere political leadership; he was often considered a divine representative on Earth, chosen by the gods to rule and protect his people. As the highest level of the social pyramid, the king held absolute power. He was responsible for creating laws, leading the army, and overseeing the vast bureaucracy that managed the state's resources and projects. The king's appearance reflected his exalted status: he wore nice clothes and jewelry, symbols of his wealth, power, and connection to the divine.

Beyond his military and legislative duties, the king also played a vital role in religious rituals, acting as the chief intermediary between the gods and humanity. His pronouncements were law, his decisions shaped the destiny of cities, and his very presence symbolized the order and prosperity of the kingdom. Royal families, including the king's immediate relatives, also enjoyed a privileged position, benefiting from their proximity to power and often holding important administrative or religious roles.

Priests and Religious Leaders: Guardians of the Sacred

Closely associated with the ruling class, and sometimes even surpassing them in influence, were the priests and religious leaders. In a society deeply rooted in polytheistic beliefs, the temples were not just places of worship but also significant economic and social centers. Priests managed the vast temple estates, which often owned substantial land and resources, and oversaw the elaborate rituals necessary to appease the gods and ensure the well-being of the community. Learn about the highly stratified social pyramid of ancient Mesopotamia, with priests at the top, kings, officials, landowners and merchants in the middle, and slaves at the bottom, highlights the central role of the clergy.

The chief priest or priestess of a major temple held immense power, often advising the king and influencing state policies. They interpreted omens, performed sacrifices, and maintained the spiritual health of the city-state. Their knowledge of sacred texts and rituals gave them unique authority, and their wealth, derived from temple lands and offerings, further solidified their position. In some periods, particularly in early Sumer, the temple was the primary economic and administrative power, owning much of the land and resources, a theory prevalent since the publication of the archives of the Bau temple.

The Backbone: Free Citizens and the Middle Class

Below the elite ruling and priestly classes lay the broad stratum of free citizens, often referred to as the "common class." This group formed the economic and social backbone of Mesopotamian society, encompassing a diverse range of professions and contributing significantly to the daily life and prosperity of the civilization. This middle class, though not as powerful as the nobility, enjoyed rights and freedoms that distinguished them from the enslaved population.

Scribes, Artisans, and Merchants: The Economic Engine

Within the free citizen class, certain professions held higher esteem and often greater wealth. Scribes, for instance, were highly valued. Literacy was a rare and powerful skill in ancient Mesopotamia, essential for administration, record-keeping, and communication. Scribes meticulously documented laws, economic transactions, literary works, and historical events, making them indispensable to both the state and private individuals. Their training was rigorous, and their profession offered a path to social mobility, albeit limited.

Artisans, including skilled craftsmen like potters, weavers, metalworkers, and jewelers, also formed a respected part of the middle class. Their expertise was crucial for producing the goods necessary for daily life, luxury items for the elite, and tools for agriculture and warfare. Merchants, too, played a vital role, facilitating trade within Mesopotamia and with distant lands. They brought in raw materials not available locally and exported finished goods, contributing to the economic vibrancy of the city-states. These individuals, often organized into guilds, could accumulate considerable wealth and influence, though they remained subject to the authority of the king and priests.

Farmers and Laborers: Feeding the Civilization

The vast majority of free citizens were farmers and agricultural laborers. Their tireless work in the fields, cultivating crops like barley and wheat and tending livestock, was the foundation of Mesopotamia's economy and its ability to sustain large urban populations. While their lives were often arduous and their economic standing modest, they were free individuals who owned their land or worked on temple/state-owned land, paying taxes or tribute in return for protection and access to irrigation systems.

Other laborers included fishermen, shepherds, and those involved in construction projects like ziggurats, temples, and irrigation canals. Their physical labor was essential for building and maintaining the infrastructure of Mesopotamian society. While their lives were characterized by hard work and dependence on agricultural cycles, they were not enslaved and held certain legal rights, including the ability to marry, own property (though often limited), and participate in legal proceedings.

The Base: Enslaved People and Their Plight

At the very bottom of the Mesopotamia social pyramid were the enslaved people. Their existence was marked by hardship, lack of freedom, and often brutal treatment. Enslaved people were considered property, not individuals, and had virtually no rights. Their lives were dictated by their owners, and their labor was exploited for the benefit of the upper classes and the state.

Slavery in Mesopotamia originated from various sources. War captives were a primary source, as defeated enemies were often brought back as spoils of war. Debt was another significant factor; individuals who could not pay their debts might sell themselves or their family members into temporary or permanent servitude. Children born to enslaved parents were also considered enslaved. While some enslaved individuals might eventually gain their freedom, either through purchase, an owner's benevolence, or specific legal provisions (though rare), the vast majority remained in bondage for life.

Enslaved people performed a wide range of tasks. Many worked in agricultural fields, enduring harsh conditions. Others served in households, performing domestic chores. Some were employed in large-scale construction projects, mining, or textile production. While their lives were undeniably difficult, there were distinctions even within this lowest class. Temple slaves, for instance, sometimes had slightly better conditions than privately owned slaves, and some skilled enslaved individuals, like musicians or scribes, might be treated with more care due to their valuable talents. However, fundamentally, their status as property meant they were subject to the will of their owners, highlighting the severe stratification of the Mesopotamia social structure.

Daily Life Reflected in Social Standing

Ancient Mesopotamia's social class determined one’s lot and reflected the daily life, habits, and appearance of an individual. The disparities between the classes were stark and visible. The nobility and wealthy merchants lived in large, elaborate homes, often constructed of brick, with multiple rooms and courtyards. They enjoyed a diet rich in meat, fine bread, and imported goods, and their clothing was made of high-quality linen or wool, often dyed in vibrant colors and adorned with jewelry. Leisure activities included feasting, music, and board games.

Free citizens, particularly farmers and laborers, lived in more modest mud-brick houses, often with one or two rooms. Their diet was primarily based on barley, vegetables, and fish, with meat being a rare luxury. Their clothing was simpler, made of coarse wool, and practical for labor. Their lives revolved around work, family, and community rituals, with little time for extensive leisure. The enslaved population, by contrast, lived in rudimentary shelters, often within their owners' compounds or in crowded barracks. Their diet was meager, and their clothing was minimal, reflecting their harsh existence and lack of personal possessions. Their lives were defined by toil and obedience, with virtually no personal freedom or comforts.

Even legal rights were heavily dependent on one's social standing. The famous Code of Hammurabi, a comprehensive set of laws from the Old Babylonian period, explicitly outlines different penalties for crimes based on the social class of both the perpetrator and the victim. For instance, an injury inflicted upon a member of the upper class would incur a harsher penalty than the same injury inflicted upon a commoner or an enslaved person. This legal framework further cemented the rigid divisions within the Mesopotamia social hierarchy, ensuring that one's birth determined much of their life's trajectory and legal protections.

The Dynamics of Stability and Change

At what period did the stable (static) social hierarchy begin to establish itself in Mesopotamia, and what forces led to this establishment, and preserved it for millennia? The emergence of complex urban centers, starting with Sumerian city-states around 4000-3000 BCE, necessitated sophisticated organizational structures. The need for large-scale irrigation projects, defense against external threats, and the administration of growing populations led to the consolidation of power in the hands of kings and priests. The concept of divine kingship provided a powerful ideological justification for the hierarchy, suggesting that the social order was divinely ordained and therefore immutable.

Economic factors also played a crucial role. The theory of state and temple ownership of all land property, prevalent in early Mesopotamian scholarship, suggests a highly centralized economic system that naturally fostered a hierarchical distribution of resources and power. While later scholarship has nuanced this view, acknowledging private land ownership, the dominant role of temples and the state in land and resource management undoubtedly contributed to the enduring stability of the social pyramid. Furthermore, the development of writing and sophisticated legal codes, like Hammurabi's, served to codify and enforce these social distinctions, providing a legal framework that reinforced the existing order and limited social mobility.

Legacy of the Mesopotamia Social Pyramid

The Mesopotamia social pyramid illustrates the intricate social hierarchy that existed in one of the world's earliest civilizations. This structure played a crucial role in the daily functioning and long-term stability of Mesopotamian society. From social structures and governance to art, literature, and technological advancements, we unravel the complexities and achievements that defined the fabric of this ancient world. The enduring nature of this hierarchy, despite the rise and fall of numerous empires and dynasties within Mesopotamia, speaks to its fundamental effectiveness in organizing a complex society.

The principles of stratification seen in Mesopotamia, with a ruling elite, a professional middle class, and a large laboring base, served as a blueprint for many subsequent civilizations. While specific titles and roles changed, the underlying concept of a tiered society, where different groups held varying degrees of power, wealth, and rights, became a pervasive model. This ancient social structure laid the groundwork for future societal organizations, influencing everything from political systems to economic distribution in regions far beyond the Fertile Crescent.

How Social Class Shaped Identity

In the Mesopotamian social structure, distinct social classes each had specific roles that contributed to the functioning of society, but they also profoundly shaped individual identity. One's social class wasn't just a label; it dictated where you lived, what you ate, how you dressed, and even how you were addressed. A king was expected to embody divine wisdom and military prowess, while a scribe carried the weight of literacy and record-keeping, and a farmer was defined by their connection to the land and its bounty.

This rigid system fostered a strong sense of collective identity within each class, even as it reinforced divisions between them. People understood their place and the expectations associated with it. While this might seem restrictive from a modern perspective, it provided a framework for order and stability in a world that was often volatile. The intricate dance between these social layers, each performing its prescribed role, allowed Mesopotamian civilization to achieve remarkable feats in architecture, astronomy, and law, leaving a lasting legacy on human history.

Conclusion: The Enduring Structure of Ancient Mesopotamia

The Mesopotamia social pyramid stands as a testament to the organizational genius of one of humanity's first complex societies. Consisting broadly of nobility, free citizens, and slaves, with finer distinctions within each, this hierarchy ensured the systematic functioning of city-states and empires for thousands of years. The king, as the divine head, and the priests, as guardians of the sacred, occupied the highest echelons, followed by the vital middle class of scribes, artisans, and merchants, and the indispensable farmers and laborers. At the base, enslaved people endured lives of servitude, their labor underpinning much of the society's prosperity.

This highly stratified social structure was not merely a static arrangement but a dynamic system that evolved with the civilization, yet maintained its core principles of order and defined roles. It shaped the daily lives, opportunities, and even the very identities of its inhabitants. By understanding the intricacies of the Mesopotamia social pyramid, we gain profound insights into the foundations of human civilization, the enduring challenges of social organization, and the historical roots of class distinctions that continue to echo, albeit in different forms, in societies today. What aspects of this ancient social structure do you find most surprising or influential? Share your thoughts in the comments below, and explore other fascinating aspects of ancient civilizations on our blog!

Social Class Pyramid Mesopotamia

Social Hierarchy Of Mesopotamia

Social Class Pyramid Mesopotamia